Why We Hate

How your ego cheats to feel superior

Jeff Bezos. Kanye West. Dubai. Some names you can’t say aloud without provoking a wave of contempt.

And yet, most of the people triggered by these names have never met Bezos, never spoken to Kanye, never set foot in Dubai. Still, they treat them like sworn enemies—rallying others to share their disdain.

Why is that? Why does the mere existence of another human being—living with different values, a different lifestyle, a different vision of the world—cause so much discomfort? Why does their success or visibility feel like a personal attack?

Because your ego can’t stand it. Their success exposes the fragility of your own worldview.

If someone thrives while living by values completely different from yours, what does that say about the validity of your choices?

Your ego cannot admit this possibility. It would mean confronting the chance that you were wrong, that your path may not be the only or the best one.

And so the defense mechanism kicks in: attack, disqualify, condemn. Bezos is “greedy”, Kanye is “insane”, "Dubai is “vulgar”. It doesn’t matter whether these claims are true. What matters is that they protect your sense of superiority.

This is why you don’t just want to succeed; you want others who live differently to fail. Your worldview doesn’t feel safe until theirs is destroyed.

Every insult, every moral judgment, every burst of contempt is not about them—it’s about shielding your ego from collapse.

Definition of Ego

Ego can be defined in many ways. For this article, we’ll take inspiration from Nietzsche’s will to power and define it as the drive to dominate, to impose yourself, to express your identity above others.

The ego is not static—it’s a force, a restless movement. It is always scanning the social pyramid, always calculating: where am I, and how do I get higher?

The moment you see someone else succeeding, your ego feels the threat. It panics. It must react, and it must react fast, to put you back on top.

The problem? Your ego is a lazy bastard.

Why sweat and struggle to compete when you can just cut the other person down with a few words?

It’s far easier to lower their value than to raise your own.

That’s why the ego has invented four defense mechanisms—psychological shortcuts that restore your sense of superiority in seconds, without effort.

They are weapons of self-deception, designed not to win reality, but to win the narrative.

Let’s explore them.

Ego Defense Mechanisms

Here are 4 really convenient ways to protect your ego without doing absolutely any effort.

Equalization

Morality Switch

Pre-Disqualification

Post-Rationalization

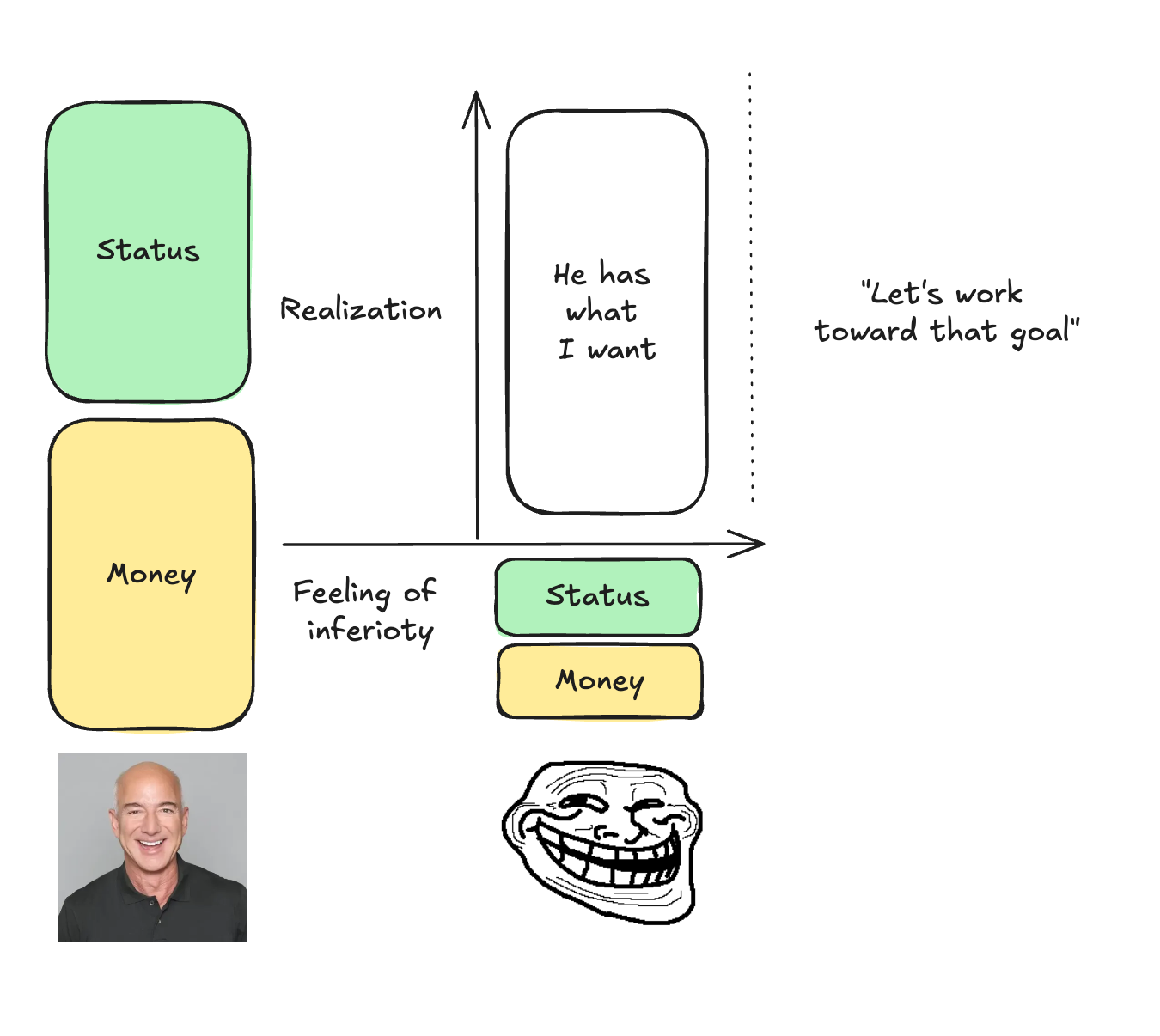

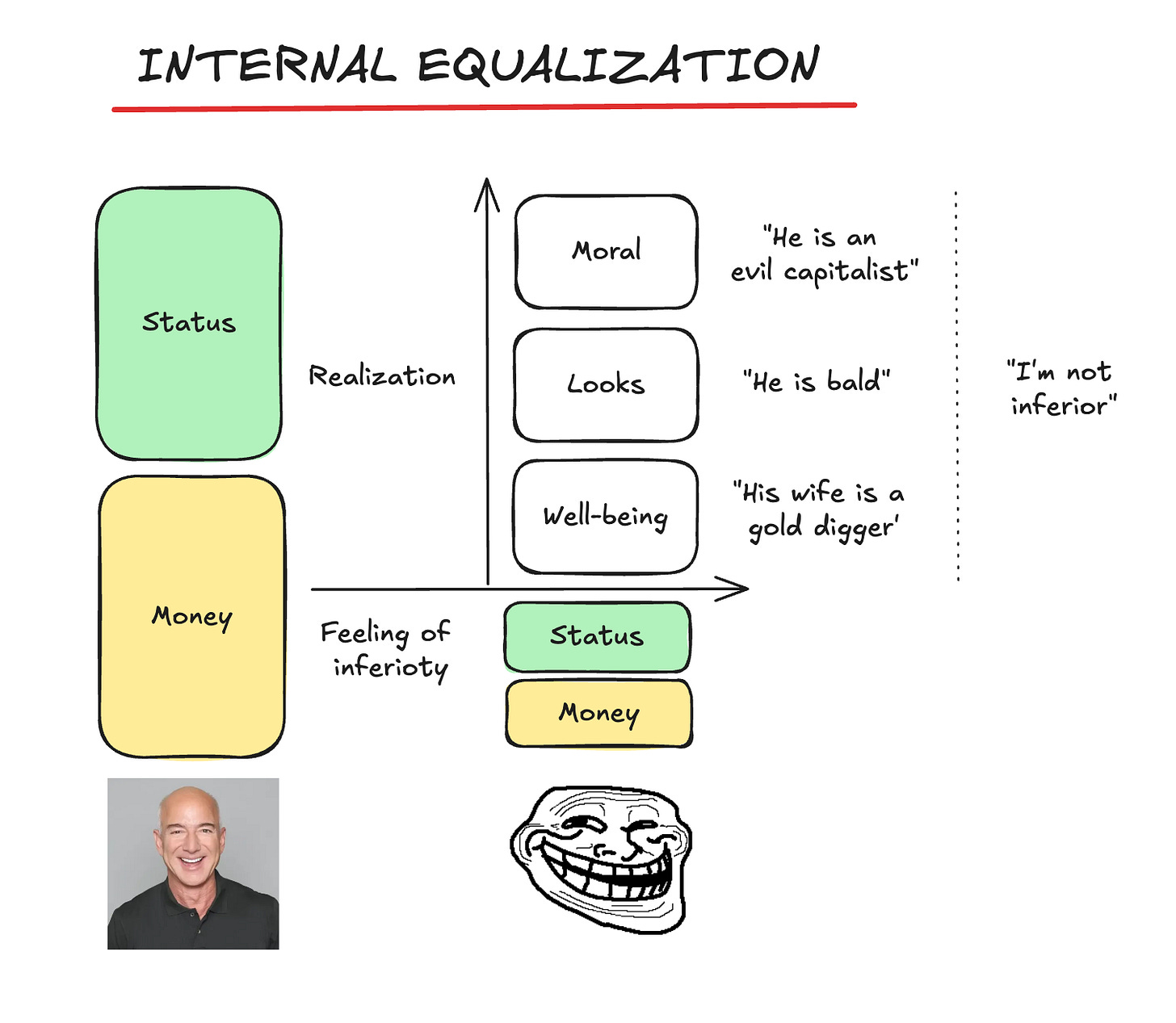

1. Equalization

“You may be rich,handsom and funny but…”

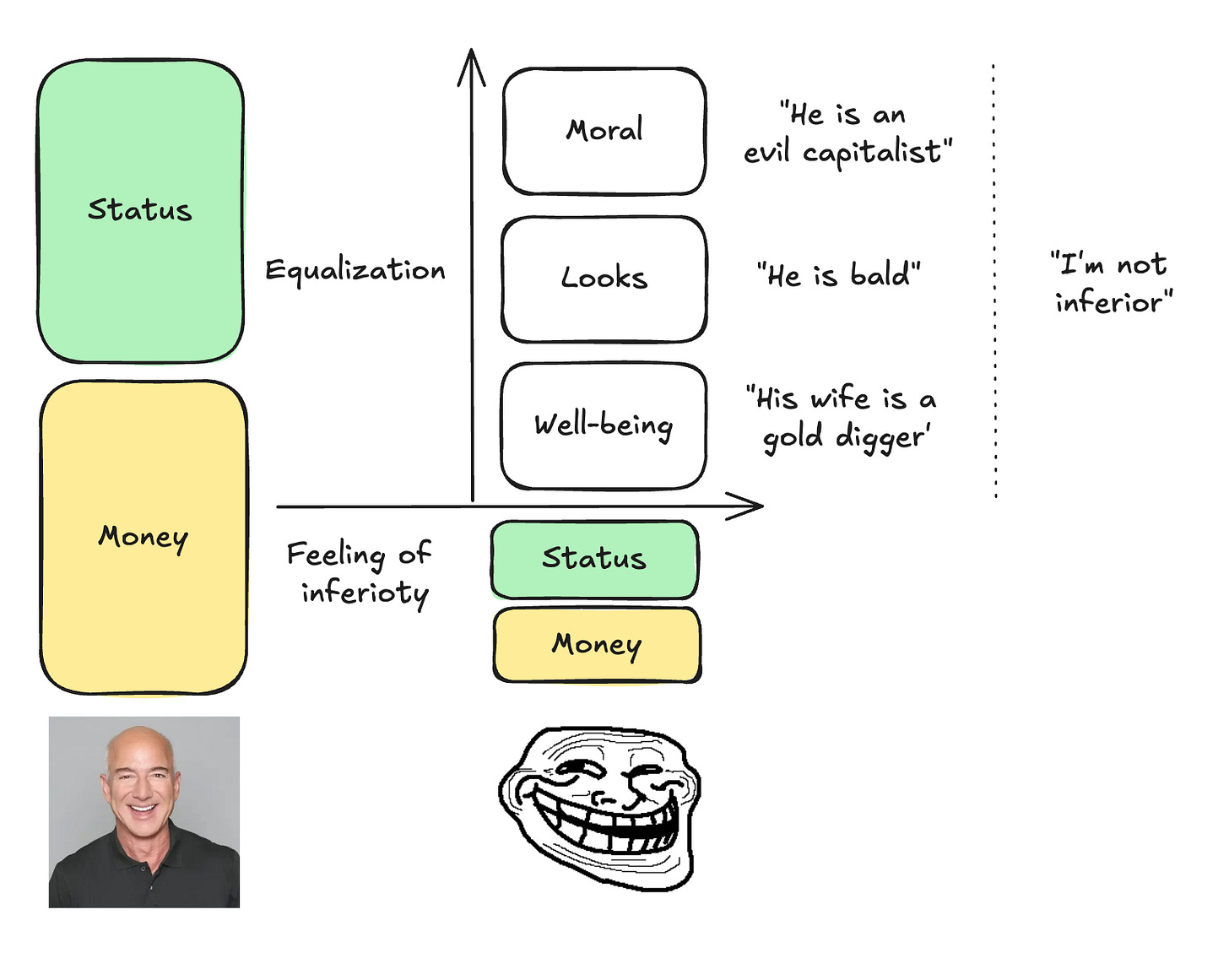

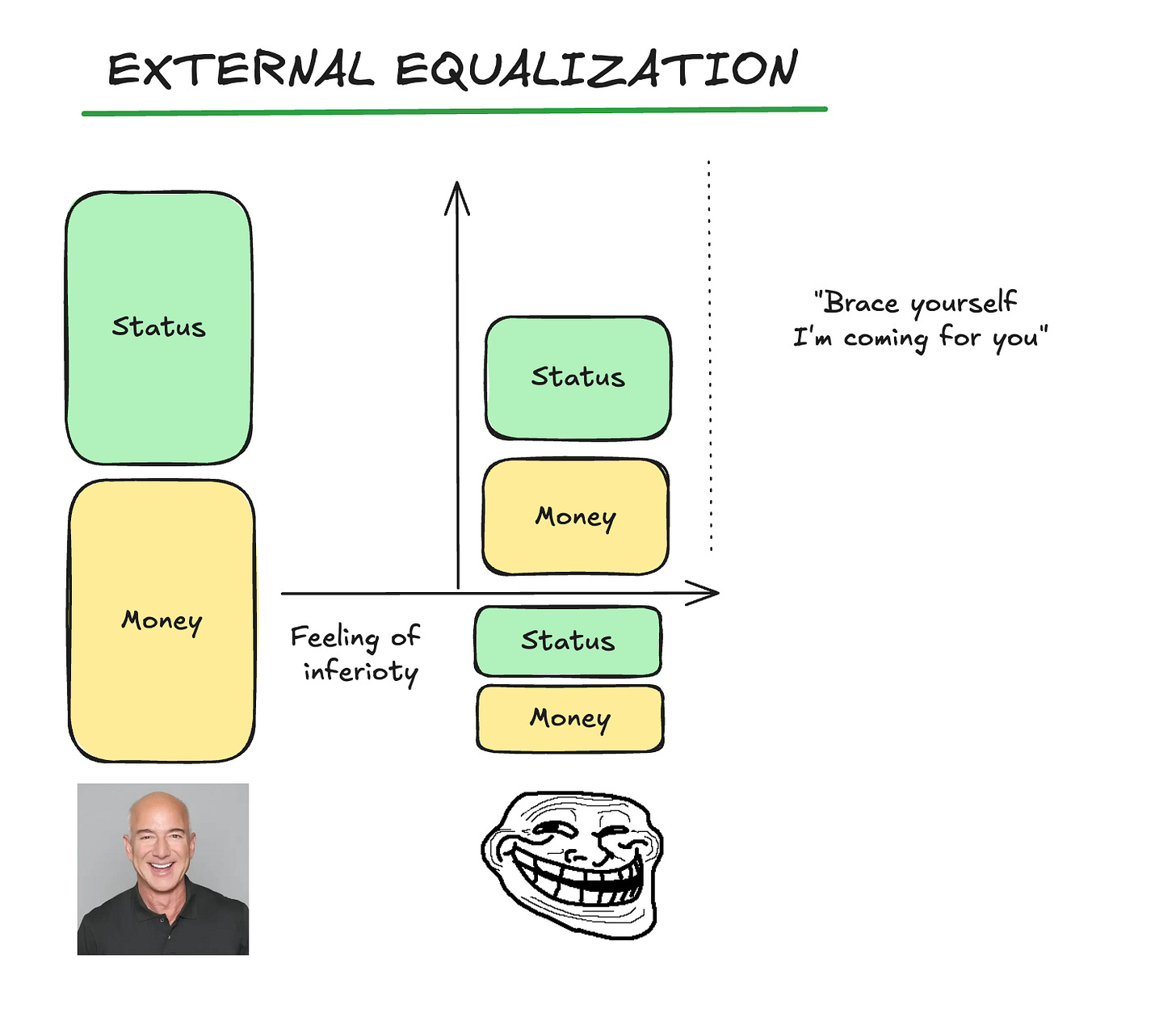

Your ego wields five levers to claim superiority: money, status, looks, well-being, and morality.

Your ego can accept to lose a battle, but it absolutely refuses to lose the war. The moment someone eclipses you in one arena, your ego instinctively try to equalize using other levers.

Your ego has 5 levers but Morality is the best because it costs nothing. To compete on money, you need to earn more. To compete on looks, you need to change your body. To compete on status or well-being, you need to climb higher or live better.

All of that takes effort.

But morality? It only takes a sentence. You don’t need proof, you don’t need evidence, you don’t even need to act differently yourself. It’s the cheapest, laziest way to win.

Artists are the toughest targets—they often excel in multiple arenas. Consequently, morality becomes an only and essential fallback.

Let’s take Brad Pitt. How do you win against that guy? You can’t. He has everything. You can only use moral.

This victory exists only in your head. Morality as a weapon doesn’t change them—it only protects you. Equalization may soothe the ego, but it never changes reality.

2. Morality Switch

“You’re winning at being the worst”

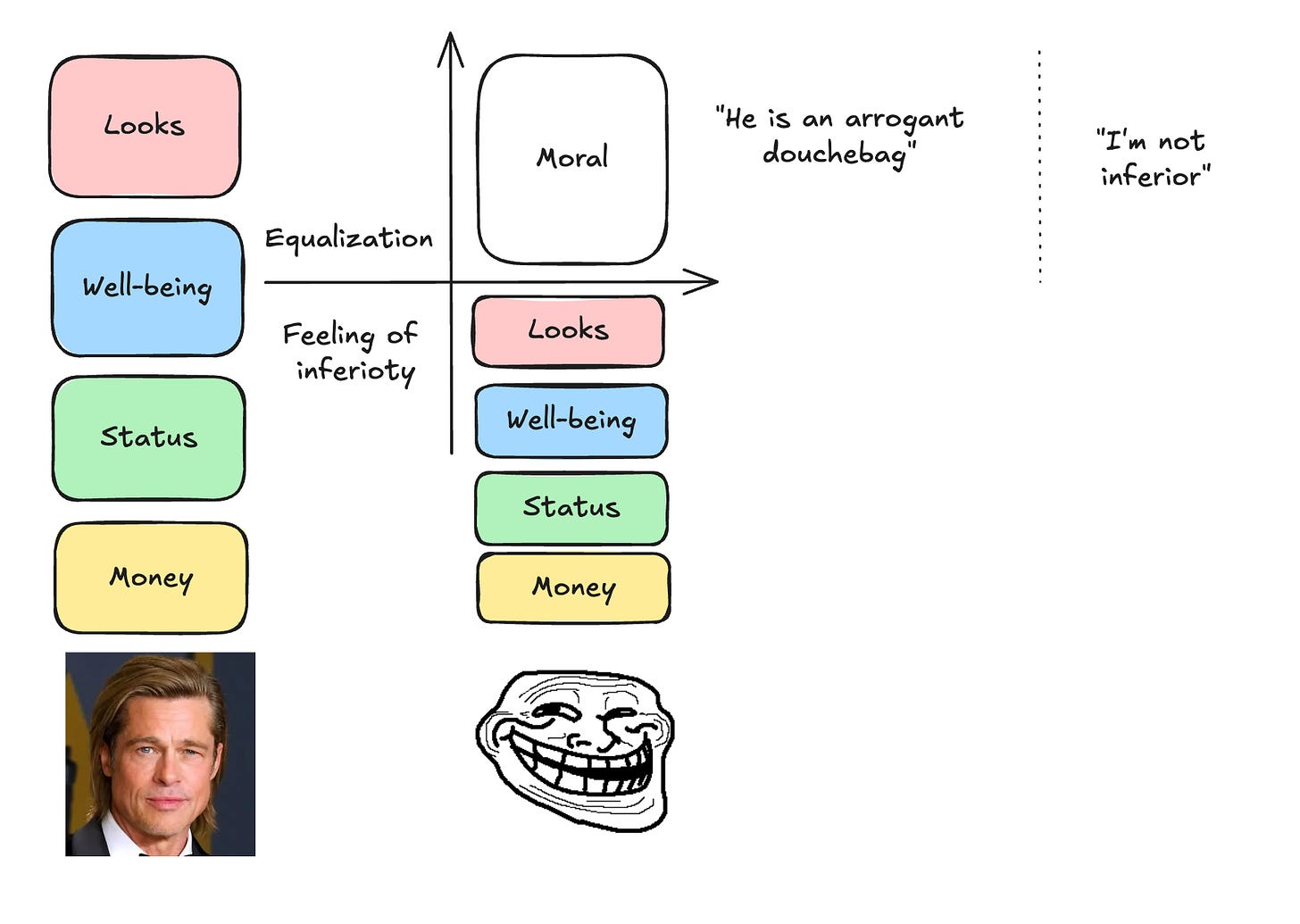

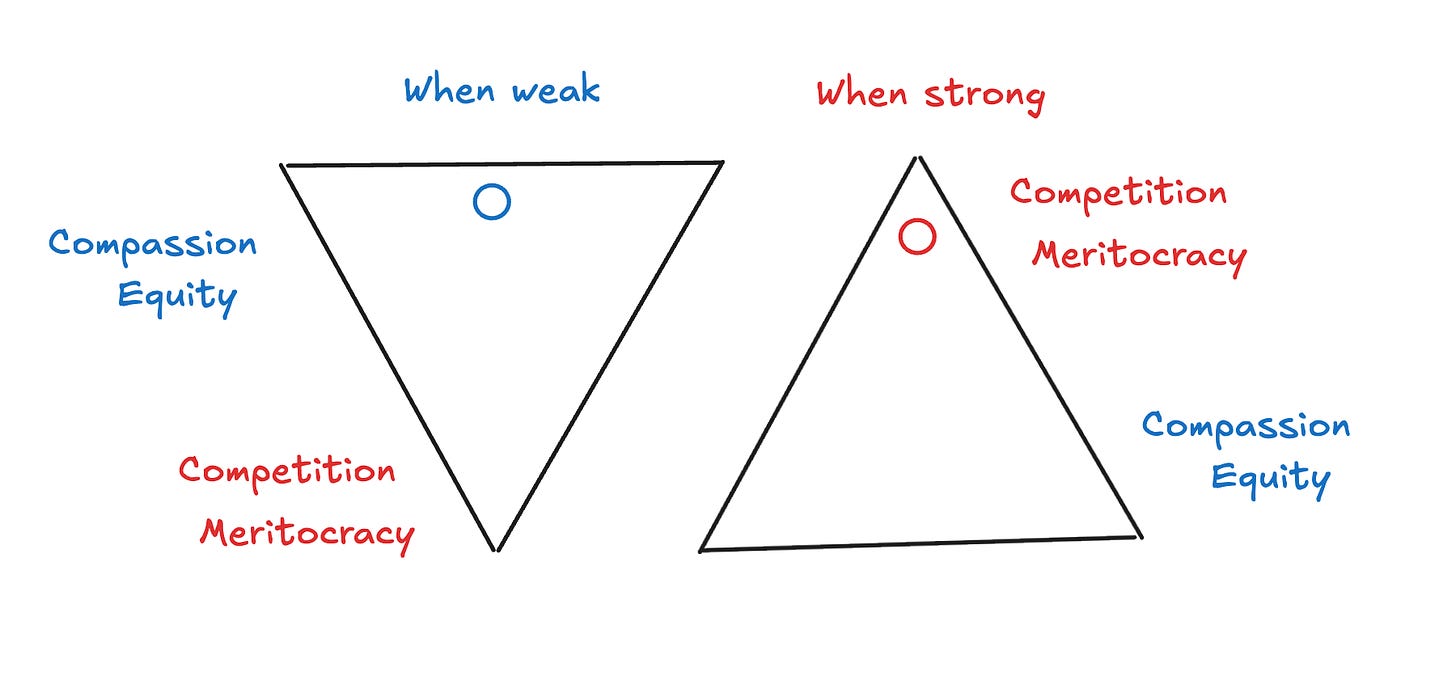

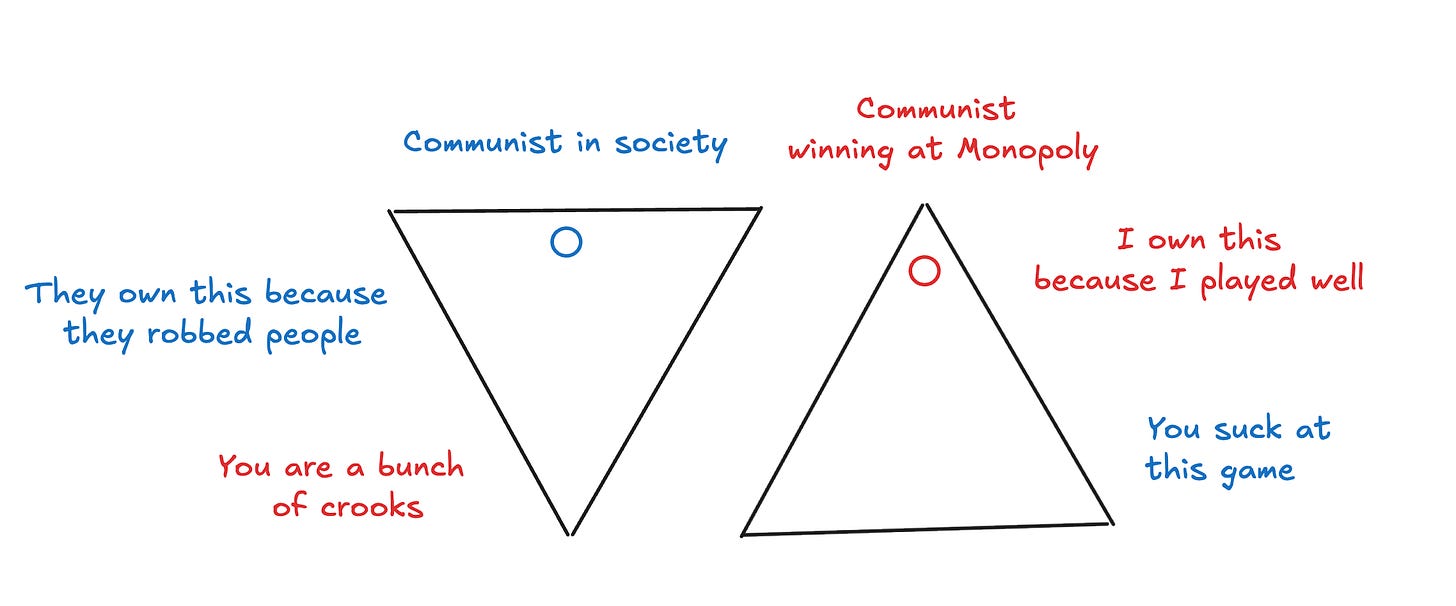

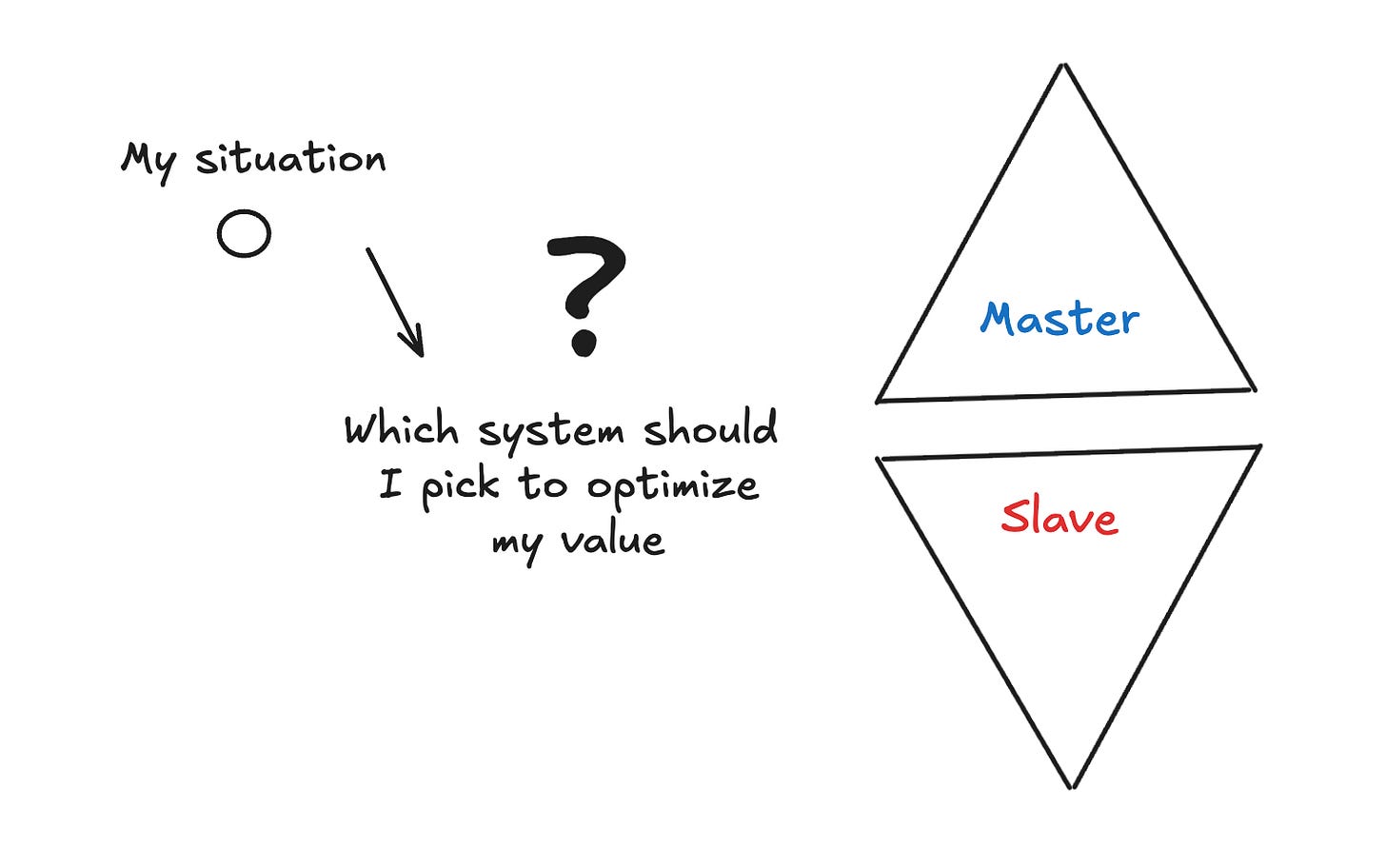

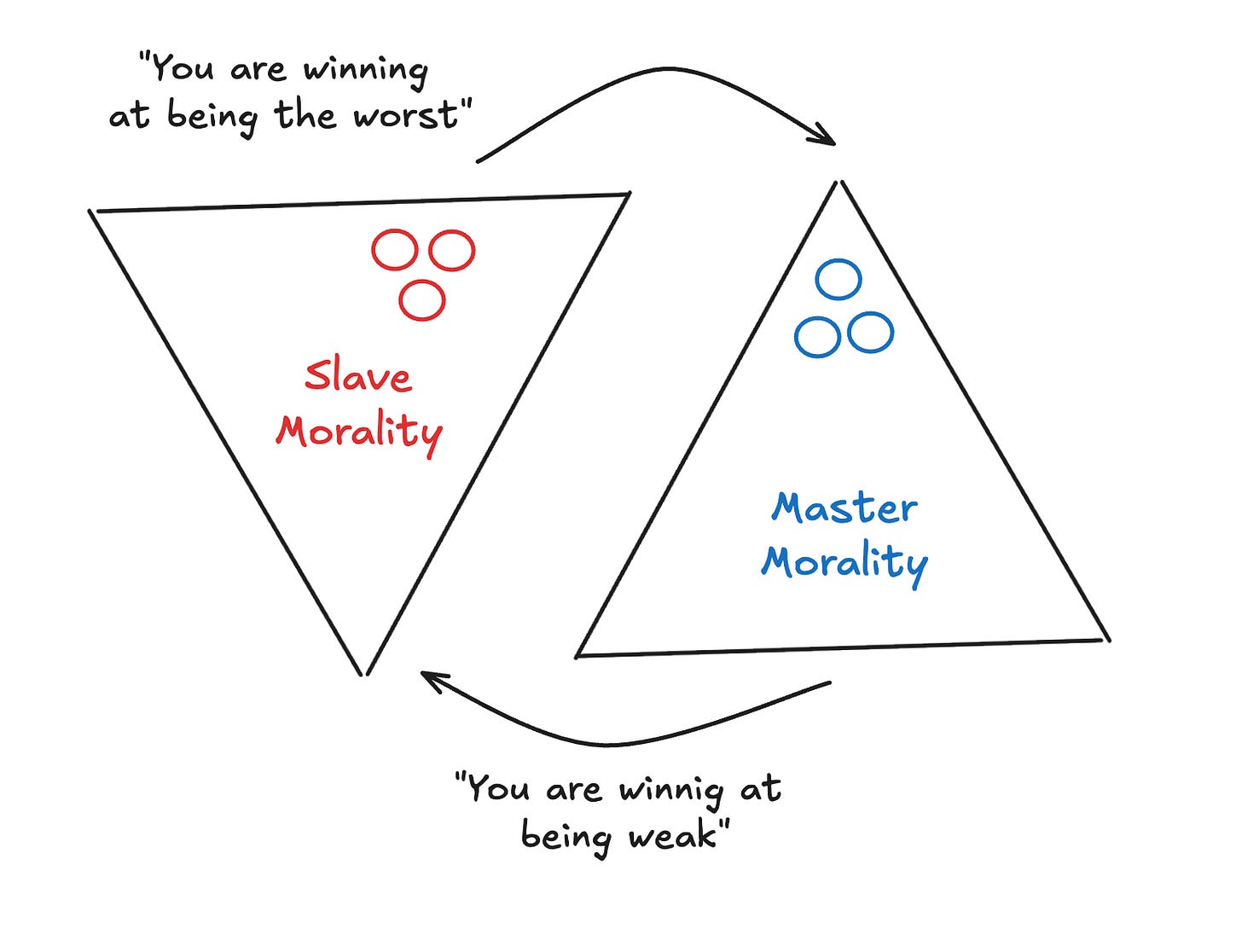

Nietzsche distinguishes between two opposing moralities.

Master morality is born from strength: pride, courage, vitality, and independence are “good,” while weakness and cowardice are “bad.”

Slave morality, born from ressentiment, inverts these values: humility, patience, and obedience become “good,” while the power of the strong is condemned as “evil.”

One affirms life through force, the other gains dignity by moral reversal.The ego moves freely between these systems, using whichever serves it best.

When weak, it clings to slave morality, painting the powerful as corrupt and elevating its own impotence into virtue.

When strong, it discards humility and embraces master morality, celebrating power, pride, and victory while scorning weakness.

Morality, in this sense, is never an absolute principle. It is a mask the ego wears to justify its position and preserve its superiority.

Desire precedes morality. We act first, then invent reasons to make our actions appear righteous. Opinions are not universal truths but defenses, built from circumstance to shield the ego.

To get a concrete example, just try to play Monopoly with your communist friend. You’ll see who is still communist after owning the most expensive street of the game.

When powerless, it is easy to call weakness virtue; when powerful, it is easy to call victory merit. Morality is not guidance but narrative—a story we tell to remain “above” others.

Each person builds a worldview that maximizes their own worth. The wealthy praise meritocracy, the poor elevate fairness. The strong glorify competition, the weak glorify compassion.

The values we uphold are never chosen for their truth but for their utility: they are the architecture of self-preservation, the framework that saves us from admitting defeat.

This also explains why we condemn those who succeed by other means. Another’s path threatens the legitimacy of our values. We do not want others to win, we want them to win our way.

The self-made entrepreneur praises resilience but dismisses heirs as undeserving, refusing to admit the role of luck, for luck would weaken the foundation of his own merit. Each guards their narrative jealously, condemning any success that does not fit the rules they must believe in.

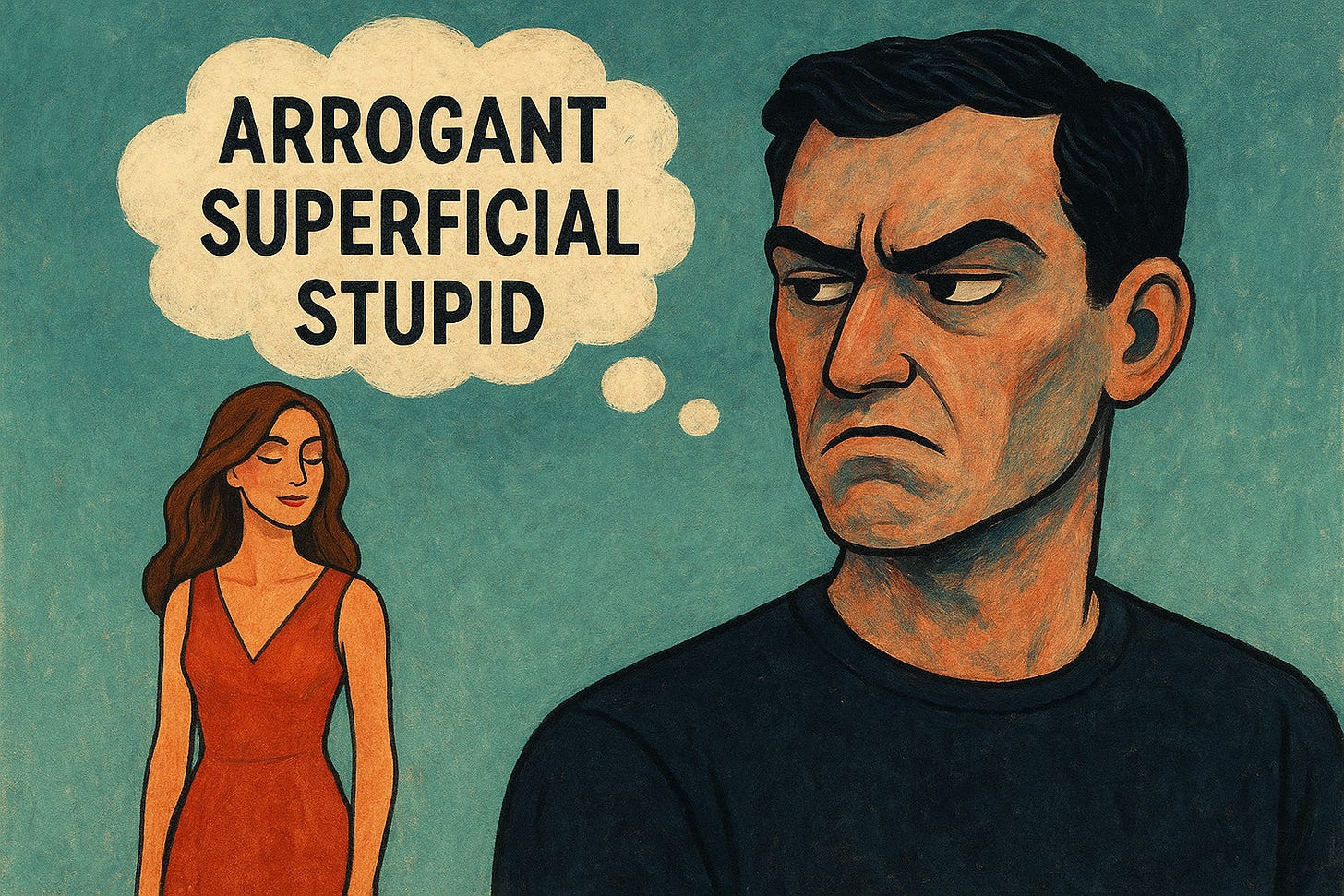

3. Pre-Disqualification

“You can’t reject me if I reject you first”

Pre-disqualification is the ego’s way of dodging humiliation. When we feel inferior, we rewrite the rules so that the person who threatens us loses value before they even have the chance to reject us.

It is not truth that matters here but protection: it is easier to believe “they are not worth my attention” than to confront “I may not be enough for them.”

The most common example is with beautiful women. A man who feels he has no chance will quickly stain her value: she must be arrogant, shallow, stupid, promiscuous.

By doing this, he avoids the unbearable thought that she could be beautiful, intelligent, and charming all at once—while still being forever out of his reach.

His criticism is not about her but about his own fear of judgment.

The same mechanism appears with wealth and status. See someone on a yacht? People rush to disqualify: he’s vulgar, he’s arrogant, probably corrupt.

Rarely do they allow the thought that he might have worked harder, taken bigger risks, or played the game better.

Because if his success is valid, then their own mediocrity stands naked. The ego prefers to imagine flaws in others rather than face its own inadequacy.

Pre-disqualification shows up everywhere:

The student who calls high achievers “nerds” to hide his own laziness.

The man who dismisses a woman as “too high maintenance” before even saying hello.

The employee who sneers at entrepreneurs as “lucky” because he lacks the courage to take risks himself.

The pattern is always the same: attack before you can be attacked.

By lowering the other’s value, the ego cushions itself against rejection. It is not that we want truth—we want safety. Pre-disqualification is the ego’s way of staying on top, even when reality says otherwise.

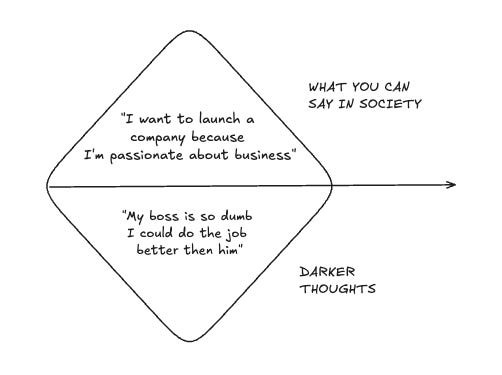

4. Post-Rationalization

“I knew that wasn’t going to work”

Post-rationalization is the ego’s way of rewriting the past to protect itself. Instead of admitting a mistake in judgment, we rearrange the facts after the event so that they fit our worldview.

You play, you get a result, and then your ego rebuilds the story around that outcome. The point is not truth but self-preservation: better to believe “I was right all along” than to accept “I was fooled.”

Think of how people react after betrayal. A woman discovers her partner cheated and says, “I always knew he was untrustworthy.”

In reality, she did not know—she ignored the signs or never saw them—but after the fact, her ego reshapes the narrative so that she appears perceptive, not naïve.

The same happens in business: after an investment fails, the investor will insist, “I had doubts from the start.” This protects him from admitting he miscalculated.

Other examples:

After losing a job, one says “I never really liked that place anyway.”

After being rejected, “She wasn’t my type to begin with.”

After failing an exam, “I didn’t even want to study that subject.”

Each time, the ego bends reality to fit the outcome. The facts are rearranged, memories edited, intuition retroactively granted.

What matters is not accuracy but dignity. The ego prefers a false sense of consistency over the discomfort of being wrong.

How To Leverage Ego

It’s possible to leverage your ressentment to bring positive change to your life. Here is how I personally use it.

Acknowledge your ego

Use ressentment as a compass

Leverage

1. Acknowlege your ego

Ego is a force—a raw energy that will exist no matter what. The real question is: do you waste it, or do you use it? Every human expression—business, philosophy, art—carries the same hidden message:

“I think I understood how life works, and I want to convince you that my vision is the right one.”

This is Nietzsche’s will to power: the drive to impose your interpretation of life on others.

Even this article is doing the same—it wants to dominate your mind.

So stop faking: “I’m all about love. I want everybody to be happy”That’s bullshit and you know it.

Acknowledge the darkest part of yourself. Take control of it or it will control you.

2. Use ressentment as a compass

Resentment is never neutral—it always hides a secret desire.

If you hate someone, it’s because they embody something you want. The opposite of hate is not love, it’s indifference. If you truly didn’t care, their existence wouldn’t bother you at all.

So instead of dismissing resentment as “negative,” treat it as a compass. Hatred is a map pointing you toward your unspoken ambitions.

3. Turn ressentment into action

Most people are too mediocre to channel their ego into creation. Being for something takes courage—it makes you vulnerable to attack.

So they choose the cheaper path: being against. Condemnation is safe. Criticism reinforces identity without risk.

But the real use of ego is to flip it from reactive to creative. Don’t let it decay into envy and cheap insults. If someone’s existence threatens you, let that discomfort become fuel.

Outperform them. Build something greater. Prove your point.

Write the book. Start the company. Make the art.

Don’t waste that energy equalizing internally—moralizing, rationalizing, or convincing yourself they don’t deserve what they have.

Instead, equalize externally—by closing the gap in reality. If they have wealth, mastery, freedom, or status and you don’t, don’t curse them. Work until you have it too.

Seen this way, resentment stops being poison and becomes propulsion. The same fire that could eat you alive can forge you into someone stronger.

Yeah, this makes a lot of sense. Kinda crazy how the ego twists things just to make us feel “right” or better than others.

aree to the part about using that energy to actually do something productive instead of just sitting in hate. Tough to do, but real.